What is power?

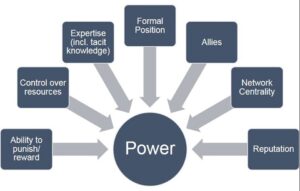

A common definition of power is the capacity to influence your environment and take decisions. From a broader perspective, power is measured as your control over valued outcomes or resources. As illustrated in Figure 1, power can be endowed by others (through networks, reputation, allies, etc.) or it can come from your expertise, your ability to punish and reward, your charisma. Although both power and leadership involve influence, power is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for leadership to exist. But status, which refers to how much others acknowledge your power, plays a key role in allowing leadership to happen. For example, Nelson Mandela still managed to motivate others to fight against apartheid even when he was in prison and had no control over any resources.

Although both power and leadership involve influence, power is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for leadership to exist. But status, which refers to how much others acknowledge your power, plays a key role in allowing leadership to happen. For example, Nelson Mandela still managed to motivate others to fight against apartheid even when he was in prison and had no control over any resources.

What is the link between power and stress?

On a scale from 1 to 7, how much stress do you currently feel in your job? A score of 1 would mean you are as cool as a cucumber, while a score of 7 would mean you are like a volcano ready to erupt. How do you think your power affects your perceived level of stress? On the one hand, the ever-increasing demands and pressure to meet the expectations that often come with powerful positions can cause more stress. On the other hand, one can also argue that because leaders have access to and control over more resources, they experience a higher sense of control, which in fine translates into less stress. Indeed, research indicates that power reduces stress. However, if that power comes under threat (for example when your job is no longer secure) the story can be quite different. In her research, Professor Jennifer Jordan demonstrated that a perceived threat to power induces stress, but only if you value hierarchy. Hence, a lot of how people experience stress is based on how they construe the world around them.

Where will your leadership journey take you next?

At IMD, we’ve been transforming leaders from around the world for over 75 years. Let us help you shape the next chapter of your success story with our high-impact leadership development programs.

How do power and stress relate to your leadership?

Possessing and experiencing power is associated with several positive effects (e.g. less distrust in the organization and work stress, but more action, optimism, abstract thinking and goal-directed behavior). However, when it is destabilized, it can have adverse consequences, such as more distrust in the organization and work stress… but not only:- Risk taking: Powerful people are deemed more likely to take greater risks and resort to risky negotiation tactics. Lack of attention to potential dangers and the search for rewards are the two main elements that encourage powerful people to engage in risky behaviors. However, Professor Jordan’s lab experiments showed that only powerful people who are in an unstable situation and have a low tolerance to stress engage in more risky behaviors.

- Power sharing: A power threat can also affect how much a leader will allow their subordinates to influence/participate in decision making. Interestingly, the negative relationship observed between a power threat and power sharing (as reported by subordinates) is driven by distrust in the organization. In other words, a leader who feels that they risk losing their power is less likely to share their power because of a lack of trust in people in the organization.

- Transformational leadership: Finally, a power threat also influences how leaders inspire and motivate their troops. Research suggests that the greater the threat to power, the less a leader applies transformational leadership (i.e. leading by doing, inspiring, fostering collaboration among work groups, etc.). In other words, when a leader feels their power is threatened, they go into a sort of “survivor mode” and effectively stop leading. This, however, is completely explained by work stress, which is not the case for directive leadership.

Box 1: What can you do to decrease the feelings of threat to your power and stress?

Relativize and rationalize. Determine whether the threat is real or just a feeling. If real, ask yourself, what is the worst that can happen? Can you accept this? If not, what can you do to accept it or minimizing the impact? Get external advice. Build and consult your trust network, rely on your experience/wisdom, take a step back to think about the situation, etc. Finding opportunities for “reality checks” is key to prevent cognitive fallacies that can go with power and help being self-aware of one’s power. Practice meditation/mindfulness. Control the monkey mind,* accept the situation and try to control the physiological effects of stress. Pay attention to the things that bring value in your life, stay positive (gratitude helps to reduce anxiety), and acknowledge that we all react differently to stress. Anticipate. Preparing for a future event can reduce uncertainty and help manage resources available to control the outcome. However, anticipation is a double-edged sword: the future is unknown and we can only have an impact on the “now.” Consider your stressor(s) from another perspective. Is “leading more subordinates” a negative or a positive stressor? What about “enlarging your job responsibilities,” is that positive or negative? Both can either trigger stress or be an opportunity to learn – depending on how you frame it! * Buddhist term associated with “unsettled; restless; capricious; whimsical; fanciful; inconstant; confused; indecisive; uncontrollable.”What can you do for your team?

Stress is contagious, so it is important to prevent your own stress from cascading to your team to safeguard their performance and well-being. One way to do this is by being mindful of the physical and psychological resources that you are providing your subordinates with during unstable times. Are they being asked to do too much with too little? Are they aware of the uncertainty around them? And if so, how can you reduce their stress? Being able and willing to see yourself through others’ eyes is a key leadership attribute. And while being authentic with your team might help you lead effectively in general, it can backfire when it comes to sharing your stress. You need to find a balance between showing your true self and avoiding the negative effects that this could entail if you contaminate your team with your stress. Your subordinates are unlikely to perceive you as disingenuous if you refrain from sharing something for their good. That said, you do need someone with whom you can share your stress and fears within the organization. This is where your trust cabinet is even more important. Overall, maintaining stability within your team and reducing uncertainty can then be crucial in a stressful context.

Find the perfect program for you.

Our diverse range of programs includes options for on-campus learning, online learning, or a hybrid/blended format combining both face-to-face and online formats.

Learn to manage your energy

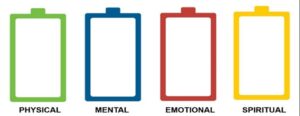

Preventing stress can be difficult. But, according to Francesca-Giulia Mereu, Coach in leadership and personal energy management, it is possible to do so to some extent by managing your own energy. A person’s total energy comes from four dimensions, referred to as batteries:- Physical (general health and vitality);

- Mental (ability to process information, clarity and focus);

- Emotional (resilience and emotional self-regulation);

- Spiritual (values and purpose in life).

These four batteries are interrelated. Everyone has a battery that depletes faster than the others, and one that charges faster. This may vary depending on the context. For example, imagine you’ve been focusing all day on writing a report. At last, you are pleased with it and send it off to your boss, who congratulates you on a job well done. As you have been seated all day, your physical battery would still be charged, but your mental one may be depleted from an extended period of concentration. Your emotional and spiritual batteries may be boosted by your sense of achievement and your boss’s appraisal.

People are often good at managing one battery and not another. Think of energy as water that evolves and fluctuates. You cannot be fully charged all the time; and of course, you would not want all your batteries to be depleted for any length of time. You need to find your happy fluctuation zone by optimizing your energy within your specific constraints. To do so, you first need to observe the levels of your different batteries and how they are impacted in different situations. It is important to learn to recognize the early signs of a battery depletion or overcharge (e.g. are you smiling less, feeling tense, have headaches?) and which of your batteries recharge or drain fastest. Then, identify two key points to better manage those batteries. For example, is a person, an activity or a memory sapping your energy? When you lack sleep, does it trigger a domino effect? What could you do to avoid these situations? To help you, why not try the tools provided in Box 2. Learning to manage your energy will help you sustain and increase your performance and quality of life and reduce your stress, which in turn will help you be a stronger and more effective leader.

These four batteries are interrelated. Everyone has a battery that depletes faster than the others, and one that charges faster. This may vary depending on the context. For example, imagine you’ve been focusing all day on writing a report. At last, you are pleased with it and send it off to your boss, who congratulates you on a job well done. As you have been seated all day, your physical battery would still be charged, but your mental one may be depleted from an extended period of concentration. Your emotional and spiritual batteries may be boosted by your sense of achievement and your boss’s appraisal.

People are often good at managing one battery and not another. Think of energy as water that evolves and fluctuates. You cannot be fully charged all the time; and of course, you would not want all your batteries to be depleted for any length of time. You need to find your happy fluctuation zone by optimizing your energy within your specific constraints. To do so, you first need to observe the levels of your different batteries and how they are impacted in different situations. It is important to learn to recognize the early signs of a battery depletion or overcharge (e.g. are you smiling less, feeling tense, have headaches?) and which of your batteries recharge or drain fastest. Then, identify two key points to better manage those batteries. For example, is a person, an activity or a memory sapping your energy? When you lack sleep, does it trigger a domino effect? What could you do to avoid these situations? To help you, why not try the tools provided in Box 2. Learning to manage your energy will help you sustain and increase your performance and quality of life and reduce your stress, which in turn will help you be a stronger and more effective leader.

Box 2: Practical examples of how to manage your energy and avoid stress

What is your current energy level? Indicate this on the battery. Which of your four batteries needs to be recharged? Try the relevant small routine exercise from the list below: Physical. Find a quiet place, stand in a comfortable position and identify which areas of your body are tense. Take deep and slower breaths, close your eyes and massage/relax these areas. Mental. Massage the junction point of the jaws, yawn as much as possible while keeping your eyebrows and mouth relaxed. Relaxing the joints of the jaws will help to free the connections between your brain and the rest of the body, and between the brain’s two hemispheres. Emotional. Make a list of your recurring sentences and choose at least two of them. Then, transform them into encouraging ones. For example, “I will never be able to be patient” could be reformulated as “I am learning to be patient.” Use the reformulation for a week (and don’t forget to encourage yourself!). Spiritual. On a sheet of paper, write down the words: couple, friendship, health, finances, professional life, family, housing, belief & values, and environment. Then, underneath each word, list what is currently contributing to your well-being. Hang up this list somewhere visible for a few days and observe how it impacts your perceptions and how you feel. Check your energy level again and notice if the level has changed. You can find more details and plenty of other practical tools in Francesca-Giulia Mereu’s book, Recharge your Batteries: Optimize your energy and be at your best, Jouvence, 2015.The power of mini-habits

Professional athletes know that recovery is key to long-term success. Indeed, it is common knowledge that regular exercise is good for your health, strengthens your self-esteem, and allows your body to dissipate stress hormones. Yet, this is often the first item that people drop from their to-do list. Preventing stress is not easy, but slight changes can trigger bigger changes. Introducing a mini-habit in your daily life could be that trigger, a first step to implement a new behavior. A mini-habit is a small action that is meaningful to you (i.e. related to something you would like to improve) and that you can do even when you are tired. What behaviors would you like to establish/change? Why is it important for you? Think about an action that you can add to a routine you already have and that will contribute to implement this new behavior, then write it down. For example, AFTER I … (e.g. brush my teeth), I WILL… (do my mini-habit: drink a glass of water, do some stretching exercises, etc.), THEN I WILL… (have a mini celebration). Finally, it is important to not let your current stress level become your new “normal.” Keep in mind that everyone is different, has their specific needs and perceives things in their own way. Being aware of these differences can already help you better understand your environment and yourself.IMD business school is an independent academic institute with close ties to business and a strong focus on impact. Through our world-leading Executive Education, Master of Business Administration (MBA), Executive MBA, and Solutions for Organizations we help leaders and policy-makers navigate complexity and change. Here at IMD, you can develop your strategic thinking skills by learning alongside senior leaders from around the world – set against the inspiring backdrop of the Swiss Alps.

Key takeaways

- Power lowers stress, but its instability increases stress. It is also important to be self-aware of your power and how it impacts your behaviors and subordinates.

- Stress is contagious and can quickly cascade to your team. Being fully authentic might not always be the best option. Reducing uncertainty and maintaining stability are critical to reduce stress within your team.

- Being able to anticipate bad events, when relevant, reduces uncertainty and stress. But over-anticipating hypothetical events that may never occur can increase stress levels.

- Your energy level can be divided into four components: physical, mental, emotional and spiritual. Learning what your chargers and drainers are and taking action to avoid excessive battery leakage will help you optimize your energy.

- There are plenty of tools available to help you better manage your energy. It’s just a matter of finding those that suit you best and using them.

- Remember, stress is a choice! As the Dalai Lama says: “If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.”