How does sustainable leadership work?

This episode takes you behind the scenes of a recent gathering led by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development together with IMD, where David Bach sat down with two sustainability leaders....

by Ben Bryant Published April 3, 2025 in Leadership • 12 min read •

Trust is foundational in leadership. It determines the quality of your interactions with colleagues and team members and the caliber of the work you produce together. Trust regulates risk-taking, experimentation, collaboration, information-sharing, innovation and growth. Trust (like money or love) makes the world go around – until it doesn’t. Organizations create and realize potential where there is a culture of trust. In its absence, creativity suffers, engagement declines, the quality of outputs worsens, and undesirable outcomes proliferate.

How you build trust is contingent on different factors. As a boss, your peers and subordinates will want to trust your decisions. They want to trust your ability to stand up and defend them, see opportunities and risks, make hard choices, and determine what is best for the organization and its people.

But it doesn’t stop there. Trust is profoundly relational and reciprocal. It involves sharing information, opinions, beliefs, and, occasionally, random thoughts and feelings. It is tied to how others see and experience you as a person, not just as a leader or through the actions you take. Trust grows when people feel comfortable expressing themselves and stepping out of their comfort zone. They learn something about each other’s inner integrity, character, values, and qualities. Getting to this level of trust isn’t easy. To know someone and to be known by others means first letting down barriers we all have, whether we are aware of them or not.

Let me ask you a few questions. When did you last hesitate to share your beliefs and opinions with your colleagues? When did you hold back on how you really felt about some issue – a work challenge, maybe, or the performance of a colleague involved in a key project? Do you routinely withhold your innermost thoughts, feelings, ideas, knowledge, or information from others? If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, the chances are that (a lack of) trust was an important factor in your decision to hold back.

How safe do others feel opening up to you? Do you find it hard to let them in for fear that their worldview may not be in accord with yours? Do they struggle to be honest with you, even though you might invite them to do so? Once again, the chances are that trust is playing a significant role in this dynamic.

We all have boundaries, and the way we manage them influences our trust in each other. Boundaries are a function of our identity: what makes us unique. They create distance between us and determine what we let out or keep in. They can be open or closed: fortresses we throw up around ourselves to buffer against judgment or attack or more permeable membranes that allow others some access to our interior world, to the feelings and thoughts we may not always automatically share. Of course, this requires a certain amount of vulnerability. Inviting others in carries risk as it gives people access to our interior world, the power to criticize or reject us, and to use what they discover for their own ends.

Figuring out how much of yourself to share and how much distance to maintain is a defining element of leadership. It’s not easy. We all build defense mechanisms, often without realizing it. Most of us dislike difficult feelings or conflict, so we deflect or compartmentalize. We suppress emotions or fall back on humor to avoid complex or uncomfortable scenarios.

This complexity and discomfort are very much part of leadership. As we rise through the ranks and the stakes get higher, so too does our exposure to situations that can make us feel fragile or vulnerable to scrutiny, judgment, or attack. While we may not want to be closed off or defensive, avoidance mechanisms act as an automatic self-protection system: our front line of resilience.

Consider the following exchange. Mark is the SVP of sales at a big corporation, and he’s talking to Lisa, who reports to him.

Mark: So, Lisa, we’ve been having a few issues this quarter, I think. Anything you think you should share?

Lisa: Well, as you know, that deal we had in Luxembourg fell through at the last moment. We just didn’t have the resources to do it justice.

Mark: I keep hearing these complaints about how we don’t have enough resources. We pay good salaries and good bonuses when we are successful. If we have people who can’t cope with a bit of hard work and pressure, we need to find new people.

Lisa (emphatically): This is a systemic problem. The team is very overworked. And, of course, it’s had a knock-on effect on the quality of our bids.

Mark (chuckling): Lisa, we are all overworked. You don’t need to play the victim. I don’t spend my day twiddling my thumbs, you know.

Lisa (incredulously): So, you are thinking we should just be working harder?

Mark (more conciliatory): Look, all I’m saying is we can’t afford to lose deals of this magnitude.

Lisa (more assertively): That’s not all you are saying, Mark. You are blaming my team for losing a deal we could never have won. We were set up to fail.

Mark: Oh, so it’s my fault? How did I set you up to fail, Lisa?

Lisa: You dump every bid onto us without filtering or selecting. Any bid is an opportunity for you, but for us … half of them are just a waste of time. We know it, you know it, but you keep loading us up.

The next day, Lisa sent her resignation letter to HR and copied Mark.

This exchange begins as a performance management conversation. But its purpose quickly becomes self-protection, primarily by finding a way to blame the other person. It is littered with defenses that are designed to protect the esteem and competence of the speaker.

Neither Mark nor Lisa can accept or take in what the other is saying, so they get stuck in a defensive dynamic that is hard to break free from. Mark’s opening question (“Anything you think you should share?”) is clumsy. It could come across as patronizing and untrusting – the kind of inquiry a headmaster might ask of a devious student – and may trigger Lisa’s defenses immediately. Lisa responds by suppressing or hiding her negative feelings and rationalizing to Mark (“We just didn’t have the resources”).

Mark responds with generalizations (“people are lazy”) and perhaps projections of his own insecurities (“Don’t be a victim”). Lisa responds with rationalizations rather than exploring what truth there might be in Mark’s comments (“Perhaps they appear lazy because they are highly demotivated”). Mark’s projections probably come from his own feelings of confusion, and perhaps they represent displaced aggression from his superiors.

Mark tries to bring the conversation back to its original purpose (“We can’t afford to lose deals of this magnitude”), but by now, Lisa’s emotions are bursting out, and she blames Mark for setting them up to fail. By projecting this onto Mark, she relieves herself of responsibility for the outcome and feels satisfied.

Not all performance management conversations are as blunt as this. Most executives get smarter and sharper at camouflaging aggression and defenses, so those kinds of responses can sometimes appear innocent. For example, the question “How did I set you up to fail, Lisa?” could be considered innocent or curious. However, an absence of trust means it is more likely to be felt as a defensive question – a denial of responsibility. The absence of trust is driving interpretations of what is said. Interestingly, the more camouflaged our aggressions, the more sensible we think we are acting. This is self-deception because even highly camouflaged emotions can usually be felt by others.

“ Instead of closing gaps and building trust and psychological safety, the conversation may have increased the distance between them. This is the risk at the heart of the dance of trust. ”

At best, this defensive dynamic serves to make us feel better by letting off steam, and we might feel somewhat righteous. But those feelings probably won’t improve performance, and they most certainly won’t leverage the potential of our relationships. The dynamic has created or reinforced boundaries between Mark and Lisa. Instead of closing gaps and building trust and psychological safety, the conversation may have increased the distance between them. This is the risk at the heart of the dance of trust.

Lisa and Mark are high-performing executives. So, why would they self-sabotage and not look for the underlying problems and solutions? The answer is the absence of trust: this discourages them from doing what they need to do – sharing, contributing, questioning, and challenging because self-protection becomes more important.

Trust is built on an expression of vulnerability with another person. The word “vulnerability” has been used a lot over the past decade, often referring to the act of self-disclosure. But it is much more than that. Vulnerability means we take a risk of being hurt or wounded. Each time we make ourselves vulnerable, we risk being rejected, mocked, or scorned. We need to be vulnerable and take risks to expose the potential of trust. After this, there is a moment of reaction or reciprocation, where the other person might also be vulnerable.

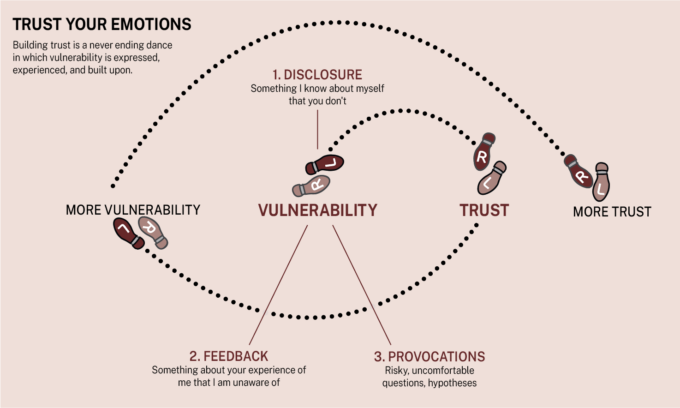

We can think of vulnerability in three actions:

1. Disclosure – something about yourself that others don’t know.

2. Feedback – something about your experience of others.

3. Provocation – something more impulsive, that will almost certainly invoke defences.

With these three actions, we not only test the nature of the trust we have with others, but we can also grow that trust. Let’s break it down.

When we reveal something about ourselves that others don’t know, it requires vulnerability: putting ourselves at risk and waiting for the reaction. This can feel uncomfortable. It’s not by chance that most of us remain pretty buttoned up when we join a new group, team, or organization. It’s only through disclosure and revealing our vulnerabilities that we move beyond seeing each other as roles or figures of greater or lesser authority, representations, or stereotypes. By sharing something honest about ourselves – something about our childhood, for example, or how we truthfully feel in the moment – we invite others to see us as humans with the same hopes and hang-ups as everybody else.

As we disclose, if we are not ignored or mocked, we nudge past our fear of scrutiny, judgment, attack, or rejection toward greater trust in our relationships – and greater faith that those relationships will endure. However, for trust to grow, there is usually a need for a reciprocal disclosure from the other person. Trust isn’t unidirectional, but we can never guarantee what another person might do.

Indeed, there is often that moment between an act of vulnerability and a response, like when you reach out to shake someone’s hand and must wait for them to do the same. That pregnant pause is where the trust is tested. The longer the wait, the more we question the trust. This is the vulnerability we experience in disclosure.

Honest feedback can be painful to give and receive, and our fear of rejection or reprisal moderates it. Often, we soften or edit feedback because we don’t want to hurt someone’s feelings, provoke anger, or risk their disappointment. How many times have you watered down your assessment of a colleague’s performance? How often have you told a white lie to spare them pain? “Thanks, Lisa, good job” instead of “Lisa, this was OK, but it feels a little incomplete in these places.” Or instead of “Mark, I understand your concerns,” how about “Mark, I understand your concerns. However, your tone is making me nervous and uncomfortable.”

Few of us enjoy giving or receiving critical feedback, but reciprocal feedback in real time is a lynchpin of building trust.

If feedback is painful, provocation can be downright grueling, requiring reserves of vulnerability and courage. This is where trust-building can so easily go wrong. As we have just seen, asking hard or challenging questions doesn’t come easily to most of us and can trigger all kinds of defensive mechanisms and behaviors. Provocation entails entering other people’s personal space and boundaries. They may be unwilling to disclose because they feel invaded or attacked, and their initial reactions might be highly defensive.

Yet, if we want to leverage the potential of our relationships, we must continuously test, interrogate, and challenge each other. Moving forward means constantly questioning assumptions and beliefs. Of course, there is a difference between provoking for the sake of it, needling a colleague or a power play, and asking hard questions to advance the collaboration toward shared goals and purpose. This may require time to allow people to digest the provocation. This is what Lisa and Mark failed to do, as Lisa handed in her resignation.

“Imagine being the captain of a ship that has hit an iceberg. If you panic and scream in terror alongside the crew and passengers, you will make the situation far worse. ”

These dynamics are a continuous play or dance in which vulnerability is expressed, experienced, reacted to, and built upon. Trust is built in the moments after people share their vulnerabilities – this is why we call it the “dance of trust”.

It can feel tempting and comfortable to play safe, especially once trust has been established. We’re often disinclined to rock the boat when we work well with someone and feel we know and trust them. But the danger is that we become too safe. In protecting the safety of the relationship, we risk neglecting its need for truth – this is where trust can start to erode.

The conversation between Lisa and Mark had the potential to be constructive and helpful, but only if trust had already been built. If this were the case, they would “trust” each other to dump their frustrations, anger, confusion, fears, and insecurities on each other along with their defenses. They would realize that the above conversation was irrational but humanly necessary. We all value civilized conversations but keeping our emotions out of our work is impossible. If there had been trust, they would have engaged in a “reset” conversation.

Let’s imagine Mark and Lisa could have that conversation. By saying, “Let’s reset”, you create a space for a more open and disclosing conversation. Next, they would need to own or take back their defenses. It might be tempting to repeatedly restate their rationalizations, fantasies, displacements, projections, and denials. But if they are aware that these are not leveraging their potential as a pair, they can work past their defenses. A more open, trust-building conversation might go something like this:

Mark: Lisa, let’s reset. I want to explain my defensiveness in yesterday’s meeting. I was feeling under quite a lot of pressure about our results this quarter, and I displaced that pressure onto you. I know that I revert to sarcasm and denial to express that.

Lisa: Thank you, Mark. I know I became defensive, too. I was so angry I just wanted to rationalize why we lost the bid. The team is not doing their best work, and I think it’s the loss of motivation. I feel responsible for that, but I also think it’s not all within my control. So, I took that out on you.

Allowing others to glimpse your real, inner self – your emotion and humanity – helps to forge better connections and deeper trust. There will be limits to what or how much you choose to disclose. Oversharing or revealing too much can undermine your authority, and there will be times when circumstances dictate that you maintain some distance.

Leadership is about building self-awareness and knowledge to figure out how much vulnerability you need to share and when it makes better sense to maintain distance, to contain your feelings, thoughts, and emotions – as well as those of others – because the situation or context demands it. Ironically, containing and keeping a distance can lead to others trusting you. This is especially important as a boss or manager, where you might need to contain or hold the anxieties of your subordinates, as well as your own. Mark displaces the anxiety he gets from his bosses onto Lisa, his subordinate, rather than containing it.

Containment and the ability to hold anxiety are as critical to your leadership as disclosure, feedback, and provocation. Imagine being the captain of a ship that has hit an iceberg. If you panic and scream in terror alongside the crew and passengers, you will make the situation far worse. Containing your emotions and holding on to dissonance gives others space to express their feelings. This is part of trust-building, too.

None of this is easy, but it isn’t meant to be. It is tough at the top. However, understanding leadership and trust as complex, relational dances – shifting dynamics that do not remain static – is the point at which leaders start to learn and grow.

Professor of Leadership and Organization at IMD

Ben Bryant is a is a highly skilled educator, executive team coach, and speaker. He is Professor of Leadership and Organization at IMD in Lausanne and Director of the IMD CEO Learning Center and the Transformational Leader program. He was previously the Kristian Gerhard Jebsen Chair for Responsible Leadership.

April 17, 2025 • by David Bach, Felix Zeltner in Leadership

This episode takes you behind the scenes of a recent gathering led by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development together with IMD, where David Bach sat down with two sustainability leaders....

April 17, 2025 • by Michael Skapinker in Leadership

All organizations should have a plan to secure trust during, after (and even before) a crisis hits. Here are a host of examples, good and bad, to learn from....

Audio available

Audio available

April 15, 2025 • by Knut Haanaes in Leadership

Writing reports that go unread, weekends wasted working on non-essential tasks, and unrealistic targets that can never be met. Top talent is being left exhausted and demoralized. Here are seven ways to...

April 11, 2025 • by Michael D. Watkins in Leadership

Michael Watkins outlines the simultaneous need for acuity and inner rootedness – what he calls Grounded Edge Leadership – to navigate increasing change and uncertainty....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience