It’s not only a question of being able to scale up production rapidly to meet unforeseen levels of demand. Take another example from the pharmaceuticals industry: Pfizer spent much of last year adjusting its sales forecasts amid plunging take-up of COVID-19 vaccinations worldwide. That led to some very difficult conversations with manufacturing suppliers.

In this new world, vertical integration of the supply chain suddenly makes much more sense. Novo Nordisk is not alone in bringing more of its manufacturing in-house so that it can exert greater control.

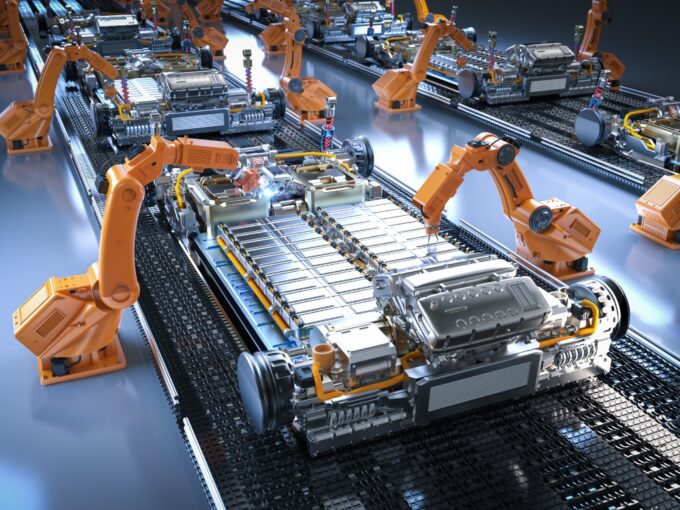

In the automotive industry, where every large company is scrambling to reorient itself toward electric-vehicle (EV) production, there is real concern about the security of battery supply. This has prompted a number of large automakers to make significant investments in EV battery factories of their own, reducing reliance on third-party suppliers.

Others in the same industry are also thinking on their feet. Tesla, for example, has invested in semi-conductor and software-engineering expertise, giving it the ability to re-program standard chips to run in its vehicles. That has given it an edge over rivals that have struggled to get hold of vehicle-ready chips at a time when semi-conductor companies have been prioritizing customers in other industries, such as mobile-phone manufacturers.

In retail, meanwhile, Amazon was an early mover in terms of implementing vertical integration. It developed an in-house supply chain and logistics operation that covers everything from warehousing to ship charters and last-mile distribution. Its aim has been to avoid vulnerability to disruption affecting third-party supply chain partners.

Disruption is the new normal

Such thinking is becoming ever more common. Business leaders had naturally hoped that the supply chain disruption they experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic would be a temporary phenomenon. They assumed that, once the world’s economies reopened, conditions would normalize. Had this been the case, rethinking their approach to supply chain management might not be necessary, given that pandemics are “black swan” events.

But it did not turn out that way. The pandemic eased, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine brought new problems. More recently, conflict in the Middle East – and the disruption that has brought to shipping in the Red Sea – has underlined the risks posed by geopolitical tensions.