Repairing reputational damage: don’t go the way of Boeing

All organizations should have a plan to secure trust during, after (and even before) a crisis hits. Here are a host of examples, good and bad, to learn from....

Audio available

by Robert Earle, Karl Schmedders Published March 27, 2025 in Sustainability • 7 min read

Imagine a world where your toaster pays you to toast your bread and your electricity bill comes with a cashback reward. Welcome to the intriguing realm of negative prices, where power plants sometimes pay users instead of charging them for the power they generate. In this economic anomaly, an oversupply of renewable energy disrupts traditional market dynamics, causing established pricing models to become irrelevant. This article will explore how wind and solar energy, combined with market constraints and the unintended consequences of well-meaning regulatory policies, are transforming the energy landscape on a regular basis, turning the act of paying for power into an opportunity to make money from power consumption.

In a normal world, you’d never imagine getting paid to use electricity. But in today’s energy landscape, thanks to a surge in renewable power generation, something rather quirky happens—electricity prices can turn negative. This occurs when there’s a surplus of electricity on the grid, often driven by abundant wind and solar power coinciding with periods of low demand. Instead of charging consumers, the market ends up paying energy companies to take the excess power off their hands. It’s a fascinating twist on the classic supply-and-demand equation, where the balance tips so far in favor of supply that the price plunges below zero.

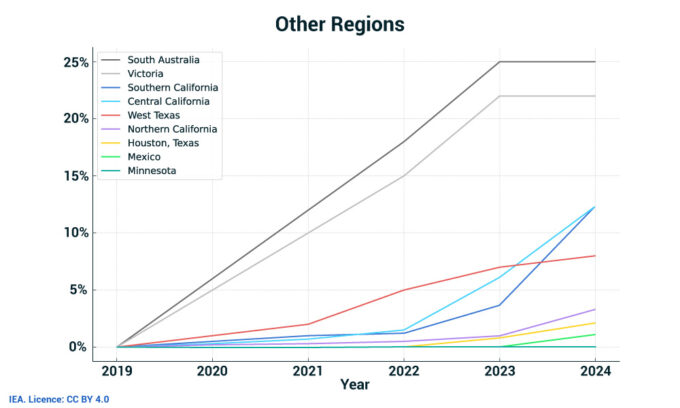

The state of South Australia has reported negative pricing for as much as 25% of the hours annually.

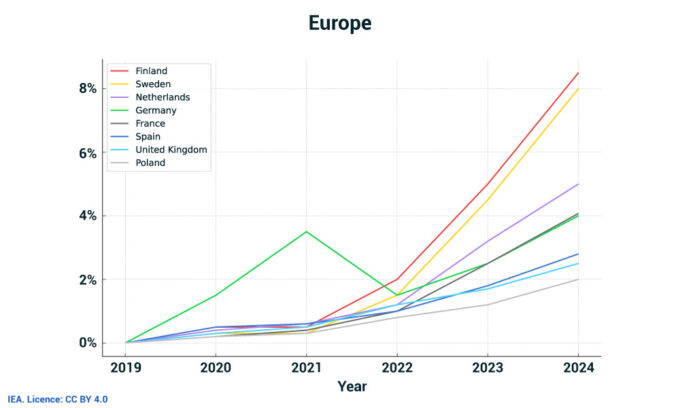

Recent years have witnessed a striking increase in the number of hours when wholesale electricity prices dip below zero. In European markets, this phenomenon has grown notably. For instance, in 2024, Finland experienced negative prices for roughly 700 hours, equating to about 8% of the total hours in a year. Similarly, Sweden saw its share of negative-price hours rise from 5% in previous years to around 7%, while markets in Germany and the Netherlands climbed from approximately 3–4% to nearly 5% of the time.

The trend isn’t confined to Europe. The state of South Australia, for example, has reported negative pricing for as much as 25% of the hours annually. Similarly, southern California in the United States has experienced a dramatic surge, with the share of negative-priced hours jumping from around 4% to 15% within a year.

Because no generation technology produces electricity at negative marginal cost (renewable energy such as solar and wind are usually considered to have zero marginal cost of production), do negative prices mean that supply-demand dynamics are broken in electricity markets?

Not at all. First, many renewable generators benefit from subsidies or fixed feed-in tariffs. For example, in Germany, wind and solar installations have historically received generous feed-in tariff schemes that guarantee payment for every kilowatt-hour produced, ensuring stable revenue even when market prices falter. In parts of the United States, renewable energy projects often take advantage of the Production Tax Credit (PTC), which provides a tax credit per kilowatt-hour, allowing them to operate profitably even under negative pricing conditions. If the PTC is USD 15/MWh, a solar generator would be willing to sell at negative prices down to minus USD 15/MWh. In other words, the PTC turns solar power into a generator with negative marginal cost.

Additionally, conventional generators—such as nuclear, coal-fired, and certain natural gas plants—often face technical and economic constraints that make it difficult to rapidly reduce output. The significant costs and operational challenges associated with shutting down and restarting these plants mean that they continue operating even when market signals indicate an oversupply.

Grid constraints further exacerbate the situation. Transmission limitations can prevent excess electricity from being exported to regions where demand is higher, worsening the local oversupply and pushing prices further into negative territory.

The bidding process in day-ahead electricity markets encapsulates these dynamics. Generators submit offers for their electricity, and when the combined supply from renewables and inflexible generation exceeds demand, the market-clearing price can fall below zero. This negative price signals that the system is overloaded and highlights the urgent need for enhanced grid flexibility, increased energy storage, and more responsive demand-side measures.

Negative pricing isn’t just a market quirk—it’s a signal that our energy systems are evolving in response to supply and demand fluctuations.

For the foreseeable future, negative pricing will remain a prominent feature of electricity markets as renewable capacity continues to expand. However, a series of concrete initiatives and policy proposals under way could mitigate its impact and even harness it as a signal for innovation.

For example, the European Commission is actively reviewing electricity market design rules, with proposals aimed at revising subsidy frameworks and feed-in tariffs while national governments such as Germany are making significant investments in grid flexibility, new battery storage, or pumped hydro projects designed to smooth out the system. In South Australia, plans for expanding large-scale battery storage projects are progressing, building on the success of earlier ventures like the Hornsdale Power Reserve.

On the dynamic pricing front, regulators in California have expanded pilot programs that allow end users to tap into real-time market prices—potentially benefiting from negative rates during periods of renewable overproduction. Meanwhile, the UK is exploring local pricing models and enhanced demand response measures to better align consumption with periods of low or negative prices. These initiatives are designed to encourage industrial consumers to shift their loads and for smart appliances to automatically optimize usage patterns.

The growing occurrence of negative electricity prices and resulting price volatility in energy markets is clearly creating opportunities for industrial users. By allowing for flexible electricity demand from their operations, businesses can turn volatility into a cost-reduction opportunity, for instance by shifting energy-intensive processes to periods of low or negative pricing to slash costs, or even monetizing excess power through storage or grid participation. Proactive firms might invest in energy storage to buffer against price spikes, align demand peaks with low-price windows to optimize spending, adopt load optimization for real-time adjustments, or engage in demand response programs to earn revenue by supporting grid stability.

Negative pricing isn’t just a market quirk—it’s a signal that our energy systems are evolving in response to supply and demand fluctuations. Imagine a future where your dishwasher gets a bonus for running at just the right moment or your electric car earns credits while charging. While the challenges of balancing supply and demand remain, the innovations in grid flexibility, storage, and dynamic pricing might just turn these odd market behaviors into a feature rather than a bug. Enjoy the ride—it’s going to be an electrifying one

Owner of Alea IE LLC

Robert Earle is a leading economist specializing in energy markets, regulatory policy, and environmental economics and the owner of Alea IE LLC, a consulting firm. With a Ph.D. from Stanford and a career spanning top consulting firms, government advisory roles, and industry leadership, he has shaped policies on electricity market design, demand response, and climate mitigation. His groundbreaking research on price regulation, infrastructure investment, and dynamic pricing has influenced policymakers worldwide. Whether advising governments, utilities, or global institutions, Earle delivers data-driven insights that drive smarter, more efficient economic policies.

Professor of Finance at IMD

Karl Schmedders is a Professor of Finance, with research and teaching centered on sustainability and the economics of climate change. He is Director of IMD’s online certification course for structured investment and also teaches in the Executive MBA programs and serves as an advisor for International Consulting Projects within the MBA program. Passionate about sustainable finance, Schmedders believes that more attention needs to be paid to on the social (S) and governance (G) aspects of ESG to ensure a fair transition and tackle inequality.

April 17, 2025 • by Michael Skapinker in Strategy

All organizations should have a plan to secure trust during, after (and even before) a crisis hits. Here are a host of examples, good and bad, to learn from....

Audio available

Audio available

April 14, 2025 • by Salvatore Cantale, Frederikke Due Olsen in Strategy

By managing ESG-heavy assets separately, companies can drive progress in their sustainable business units while addressing the sustainability challenges of traditional assets. Here are four effective strategies to achieve your goals....

Audio available

Audio available

April 10, 2025 • by Sander van der Linden in Strategy

It’s possible to immunize people against false or manipulated information through simple exercises that policymakers and platforms could easily roll out....

Audio available

Audio available

March 26, 2025 • by Didier Cossin, Yukie Saito in Strategy

Hannele Jakosuo-Jansson, Executive Vice President of People and Culture at Neste – the world’s largest producer of renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) – and a board member of Finnair, has...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience