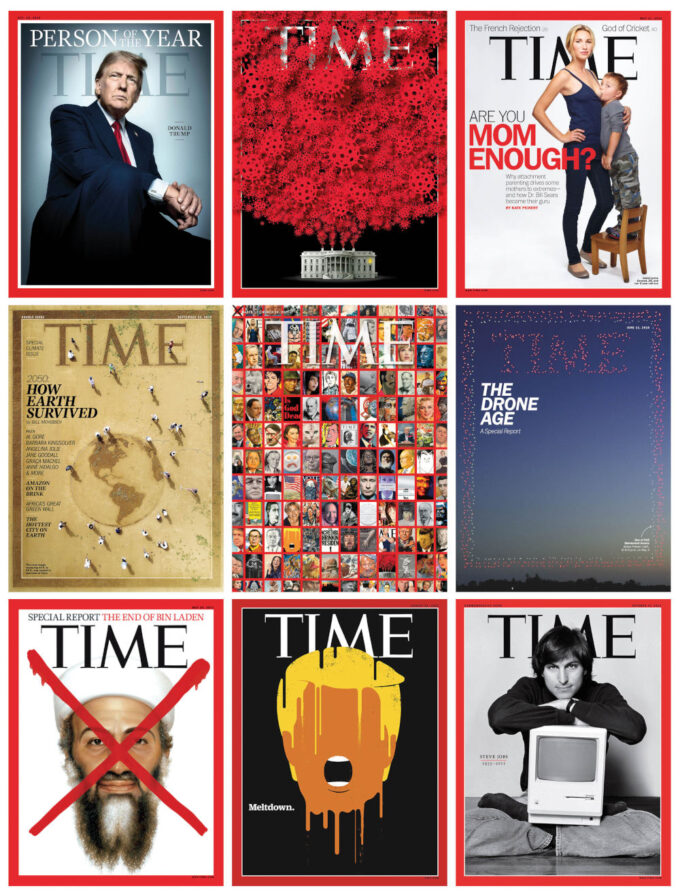

Those constraints also include limiting my tools. I use two fonts – a specially designed serif typeface called Haffner and a commonly used san serif called Franklin. This constraint helps me focus on what we want to say and how we’re going to say it visually. I limit my color palette to black, white, and red. I don’t have to spend time thinking about those things – it’s like walking into an ice cream shop with 31 flavors and knowing I will always order the mint chocolate chip.

Simplicity brings focus. But it requires a mastery of restraint – the ability to decide what to remove and what to leave untouched. It’s not just about using fewer elements; it’s about using the right elements in the right way. Every detail matters, even if it appears minimal.

A recent example of this visual simplicity is our cover of Elon Musk sitting behind the resolute desk (24 February). The image, which garnered worldwide media attention and a response from US President Donald Trump, was simple. The cover story focused on the many ways Musk, who is not an elected official, was amassing power as he and his team began dismantling the federal government. We tried several headline directions and had other visual elements sitting on the desk, but in the end, it was important to be visually clear – Musk, holding a mundane cup of coffee, comfortably seated in the world’s most powerful chair.

Creativity thrives in simplicity. When faced with limitations, it’s easy to get caught up in trying to do everything at once. Focus on the most important aspects of your project, stripping away the unnecessary. It’s about finding ways to turn the noise into something powerful and impossible to ignore, much like the Rauschenberg paintings.

2. Trust the process

I am often asked where ideas come from. It’s not an easy question to answer, but I’ve learned they typically don’t come from brainstorming meetings or ideas sessions. They can happen anytime, anywhere, often when you’re not even thinking about them. Inspiration can strike while walking down the street, taking a shower, observing trends, or through persistent trial and error. Ideas are born from a seemingly endless combination of sources.

Usually, my first ideas on a project turn out to be the best, but creativity can also take time. Constraints may lead to frustration, but it’s crucial to trust the process and keep refining the idea. Breaks in the action are beneficial, and distance from a project allows you to return with a fresh perspective. Even during stressful deadlines, I would occasionally leave the office (Central Park was close by) for a short walk to clear my head and trust that new ideas would emerge. And they always did.

However, having lots of ideas doesn’t mean they should all survive or be presented. During my first few years at TIME, I worked hard to present dozens of different options and visual directions for the editors to choose from, thinking I was doing them a favor by offering lots to choose from. I didn’t realize I was just inundating them with more images. It took some time for me to understand that the value I added was in visually editing the process.

Ideas also benefit from collaboration. When working with artists, I generally suggest a direction they should explore, but I always want them to bring their talents and thoughts to the project. Creating visuals in isolation is challenging when the aim is to resonate with a wide audience. And while collaboration often yields the best results, it’s also important to strike a balance. The phrase “too many chefs in the kitchen” is certainly apt when it comes to design.

Visual – and creative – simplicity involves a great deal of thinking, but don’t overthink it. Limit your options (mint chocolate chip). Be bold and memorable (Rauschenberg). Trust the process (a walk in the park). Just a few simple steps to help us all grab people’s attention and hold it.

Audio available

Audio available