How family enterprises can navigate adversity and build organizational fortitude

Fire, floods, relocation, and a pandemic couldn’t sink Formans, the family-run smoked salmon supplier. Here’s how they stayed afloat....

by Marleen Dieleman, Camellia Pham Published April 19, 2024 in Family business • 8 min read

Although we like to think of ourselves as rational decision-makers, an expanding volume of research suggests that biases cloud our judgment and influence our decisions. In the context of top management, overconfidence bias has gained the most attention. This is because high-level executives, such as business owners and CEOs, are tasked with making tough judgment calls when it comes to strategic decisions involving risks.

While risk-taking is essential to get ahead in business, overconfident executives take more risks and tend to forego the flexibility to re-adjust their strategy. It’s worth considering how to avoid overconfidence as erring on the side of too much risk can put the company on a path to failure.

How vulnerable a top executive is to biases depends on two types of circumstances: the industry context and the company’s decision-making processes.

In terms of industry context, researchers find that there is greater scope for erratic decisions in volatile environments. In unpredictable environments, it falls to the top executive to interpret ambiguous information, leaving more room for biases than in predictable settings.

In terms of decision-making processes, top executives with more power are more prone to bias. More control over decision-making presents fertile ground for biases because it comes with a lack of checks and balances that would usually force discussion and reconsideration.

In the maritime industry, business owners typically face both settings. For instance, as it is a capital-intensive industry, buying a vessel is a strategic decision that often involves incurring debt. Yet you cannot be confident about future earnings due to volatile market cycles. Beyond market volatility, the global nature of maritime businesses also comes with geopolitical and environmental risks, including Somali pirates, US sanctions, or draughts, reducing access to crucial waterways such as the Panama Canal.

Moreover, most companies in the maritime industry are family businesses. Family firms have advantages, such as speed of decision-making and the ability to take risks. Owners of family-controlled companies often also play a role in strategic decisions. By virtue of ownership and authority in the company, owners’ level of power is extremely high – they often call the shots.

This means that the maritime industry is a textbook setting for overconfidence bias to become a very real issue.

Overconfident leaders typically share a few features: they overestimate their abilities, they interpret ambiguous data as aligned with their strategic decisions, they think they are better than their peers, and they display great certainty when further inquiry is warranted. As a result, they take more risk and forego investments in a backup plan.

Although most people think of overconfidence as something dangerous, recent research suggests that overconfident CEOs are associated with better firm performance. Overconfident leaders surpass their more cautious counterparts exactly because of their willingness to take risks, while also exhibiting greater persuasiveness, persistence, and effectiveness in driving organizational change.

However, studies suggesting that overconfidence is a good thing on average have not yet considered cyclical and volatile markets, where overconfidence is so dangerous that it can spell the end of a company. Moreover, it is well-known that being in a downturn or a positive market cycle matters for how overconfident top executives take risks.

Thus, a better question to ask is: when in a cyclical market is overconfidence a serious problem? We suggest two concrete patterns where overconfidence can lead to a company’s downfall: 1) Inexperienced executives during market expansion, and 2) Experienced executives during a downturn.

In cyclical markets, it is the decisions you take when times are good that determine whether you can survive a market downturn. Seasoned executives, drawing from their wealth of experience, may have gone through a downturn before and thus recognize the pitfalls of aggressive risk-taking when the cycle is favorable. Less experienced executives, especially founders, may be buoyed by their success and by positive market signals. It is these inexperienced maritime owners that are most likely to succumb to overconfidence.

We call this the Icarus problem.

“Overconfident leaders tend to overestimate their abilities, interpret data to support their decisions, and exhibit great certainty, resulting in more risk-taking behaviors.”

Seasoned executives in the later stages of their careers, however, may also succumb to overconfidence. They are more likely to do so in a downturn because business owners hate to end a successful career with a greatly diminished economic and social status.

Research suggests that executives take risks more aggressively towards the end of their careers as they may not be around to see the benefits of a more measured approach. Moreover, behavioral studies suggest that when a situation is framed negatively (e.g., a threat to business survival), leaders are more willing to take risks than when presented with opportunities. ]

This is even more so among family business owners, who are known to take great risks to save their family business, for it has not just economic but also emotional value. Thus, owners facing a market crisis towards the end of their careers may doom their firms by striving to regain former glory through aggressive tactics.

We call this the King Midas problem.

One solution to the Icarus and the King Midas problems is to implement more checks and balances, but that would limit the speed and decisiveness that have served maritime owner-run companies so well. Experiencing market cycles more than once will also help, but that is unlikely as maritime cycles can take many decades to unfold.

Another promising solution is what scholars call metacognition – thinking about how to think. Executives can do this by systematically asking: Why did we take this regrettable decision that seemed right at the time? Research reveals that executives who systematically reflect on possible biases clouding their judgments make less erratic choices.

Systematic reflection does not come naturally to most people, especially action-oriented business owners. One fairly easy solution can help: Keeping stories alive in the organization about prior successes and failures. Family businesses have a unique advantage in this regard: the ability to leverage transgenerational family experience. We argue that storytelling can activate systematic reflection and augment an individual’s experience.

Storytelling is an action that forces executives to reinterpret prior knowledge in a new light. Research finds that narratives play a crucial role in shaping how family members take risks. Exposure to stories can stimulate both seasoned and inexperienced executives to develop metacognitive abilities. Narratives help executives reflect because they link decisions about the future to past experiences.

It is not just remembering and listening to stories; even better is the act of retelling stories. When executives recount stories of prior successes and failures, they are forced to reinterpret the past – a useful process scholars refer to as rhetorical reconstruction. Reinterpreting past narratives is a form of metacognitive engagement, resulting in less bias.

While storytelling is important in all organizations, it is particularly relevant for maritime companies, as the collective wisdom embedded in (family) stories can help executives identify cause and effect patterns over a longer time frame. We suggest that maritime owners can enhance their own experience through stories in two ways: second-hand experience and third-hand experience.

Second-hand experience can be gained by interacting with seniors and reinterpreting their stories – especially stories that touch on overconfidence. Structured interactions, such as regular board discussions or mentorship relations, can stimulate a reflective mindset and mitigate overconfidence bias when it matters. This is particularly relevant to the Icarus problem currently plaguing inexperienced leaders in an expanding market.

We also recognize the influence of third-hand experience, where other executives’ experiences are transferred indirectly through often ritualistic narratives of a more distant past that are remembered and retold when debating crucial decisions. This is particularly relevant to address the Midas problem that may plague experienced seniors in a downturn.

Thus, telling stories can unlock reflection and augment first-hand experience with second-hand and third-hand experience. This is particularly important for owners in cyclical and volatile industries, where the threat of overconfidence bias is high and where the necessary direct experience can only be accumulated over decades.

Top executives are not rational – their strategic decisions tend to be biased. These biases are amplified in unpredictable markets and when executives enjoy more power – a typical context for maritime owners.

One significant bias is overconfidence. While overconfidence generally has positive effects, it can endanger cyclical maritime businesses, particularly under two scenarios: 1) Inexperienced overconfident executives in an expanding market, and 2) Experienced overconfident executives in a downturn.

One solution is to systematically think about how to think (i.e., metacognition). Storytelling can activate this reflective process. Family-owned businesses are at an advantage if they leverage second-hand experience (stories from seniors) and third-hand experience (historical narratives).

Maintaining a strong (family) business legacy through narratives activates reflection. This is a powerful risk-mitigation tool to help maritime owners future-proof their companies.

Peter Lorange Family Business Professor

Marleen Dieleman holds the Peter Lorange Chair in Family Business. She is an expert on the challenges faced by emerging market enterprises in their strategic trajectories. Her research focuses on the governance, strategy, internationalization, innovation, and transformation of business families in emerging markets, and also on emerging market state-owned enterprises and the interaction between these companies and their governments. At IMD, she directs the Future-Proofing your Business Family program and is co-director of the Orchestrating Winning Performance Program.

Research assistant at IMD

Camellia Pham is a research assistant at IMD and an undergraduate student at the National University of Singapore pursuing a Bachelor of Business Administration degree, specializing in Finance and Business Analytics.

Strengthen your family’s business and governance roadmap

March 19, 2025 • by Alfredo De Massis in Family business

Fire, floods, relocation, and a pandemic couldn’t sink Formans, the family-run smoked salmon supplier. Here’s how they stayed afloat....

February 19, 2025 • by Alfredo De Massis, Cristina Bettinelli , Manisha Singal , John Davis in Family business

The survival of family businesses is at stake due to inadequate board management and the difficulties faced by leaders of family businesses in juggling various roles....

February 12, 2025 • by Marleen Dieleman in Family business

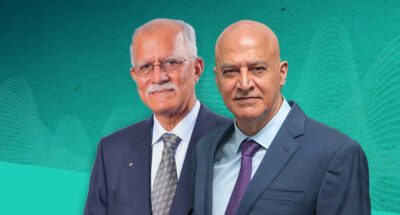

Tolaram, the Singapore-headquartered family business, has global interests in logistics, consumer goods, and technology. Family members Mohan Vaswani and Sajen Aswani discuss the company’s values-based system of meritocracy, the family’s move to...

January 31, 2025 • by Alfredo De Massis, Emanuela Rondi, Vittoria Magrelli , Francesco Debellis in Family business

Tradition is defined as the transmission of customs or beliefs from generation to generation. Innovation is the process of changing something established by introducing new methods...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience